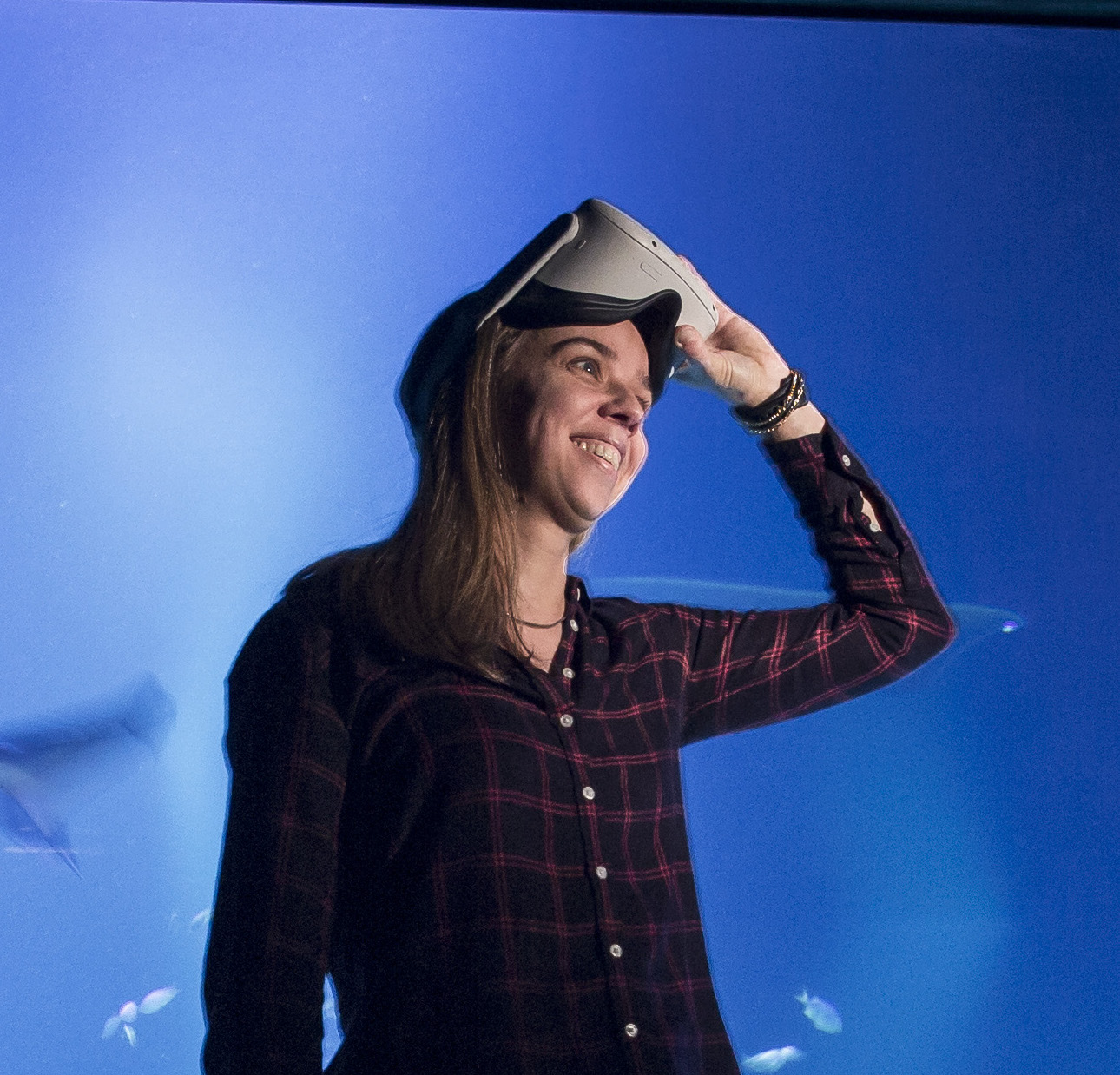

Experiencing underwater VR with Géraldine Fauville

This article is part of the blog series ‘Meet the members’ in which you’ll get to know the EMSEA members, what drives them and what inspires them. They’ll share their experience, their good practices, their challenges. They’ll talk about what ocean literacy means to them and how they hope to reach it. Today we meet Géraldine Fauville, once co-founder of EMSEA and now Associate Professor at the Department of Education of the Swedish Gothenburg University.

As a child, Géraldine devoured books about the ocean, watched every marine documentary she found on TV and absolutely adored Cousteau. Yet, it was not her parents that introduced her to this world, nor the (lack of) attractiveness of the grey, sandy Belgian North Sea that lured her. It was some inexplicable, innate passion that eventually led her to become a marine biologist as quickly as possible.

Géraldine’s career

After her studies, Géraldine moved to Sweden. There, she became involved in an educational project – a collaboration between the University of Gothenburg and Stanford University – to create and implement computer-based tools for environmental education on climate change and ocean acidification. ‘But suddenly I realised: all people involved in the project were marine scientists. Our team knew little about research in education,’ Géraldine looks back. Therefore, she contacted the Department of Education at the University of Gothenburg, where she found researchers in education interested in the project she was leading.

It was the start of a whole new journey for Géraldine. She enrolled in a Master program in education and IT, for two years combining those studies with a full-time job and a couple of young children running around in the house. After another four years of doing her PhD, she realised she wanted to keep working with both the ocean and technology. Therefore, she moved to Stanford University for a postdoc on virtual reality and environmental education.

But then, COVID hit and the whole world came to a standstill. It was no longer possible to invite people and organise live experimental VR-sessions. People around the globe switched to other means of communication, one of which was Zoom, which quickly led to ‘Zoom fatigue’, something Géraldine and her team decided to research during Covid. ‘It was frustrating, that Covid period. Suddenly we were stuck behind our computers, unable to finish our research. We just had to do something. That research on Zoom fatigue, trying to understand it from a psychological point of view… It wasn’t something I thought I would do with my life, but it ended up being really interesting and I was grateful to be doing something productive during those Covid years,’ she reminisces.

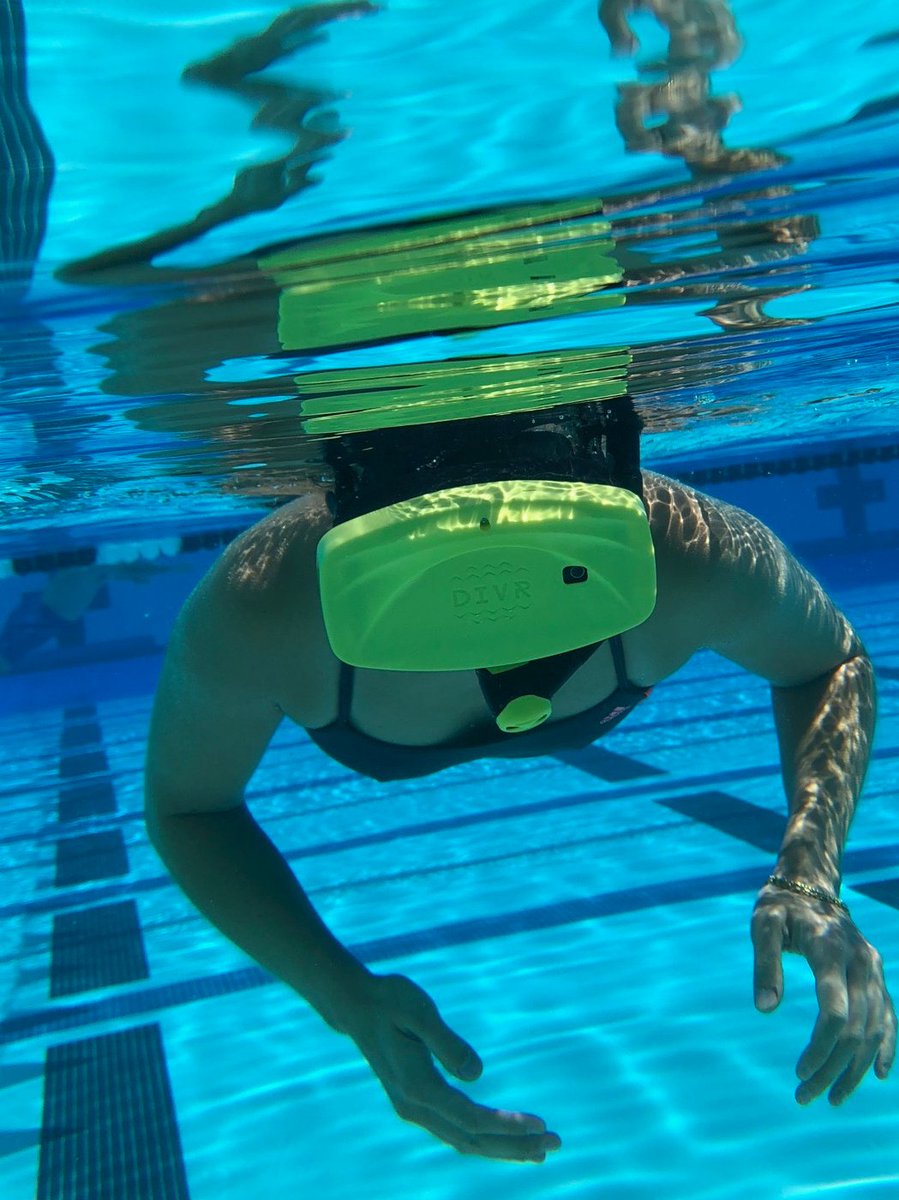

After two years of Stanford, Géraldine returned to Sweden to become Associate professor at the University of Gothenburg and to finally go back to her research on immersive technology and ocean literacy. The focus of her current research is underwater VR and she is now investigating the difference between experiencing an underwater video either standing on the ground or floating in the water.

Underwater VR

We all know VR. You put on a headset, see an animated 360-degrees-video and your mind gets tricked into believing you’re actually there. That experience is called ‘presence’. However, when you’re standing on the floor while seeing an underwater world, your mind gets confused because the sensory input on your body is completely wrong. Your skin doesn’t get wet. Your balance is too firm. You’re not floating or drifting but still experiencing the weight of your body on your feet as gravity is pulling you down. Even though you see coral reefs and sharks, your mind keeps telling you something’s off. There’s a disconnect.

That is where underwater VR comes in. ‘Not only do you see yourself moving through the water and drifting with the current, while you encounter coral reefs and turtles and sharks; but you also physically get wet,’ Géraldine explains. ‘You’re in your bathing suit, in the water, breathing through a snorkel.’ Being in the water, helps trick your brain into believing you’re actually there. ‘It seems to work. When sharks approach, people swim the other way quite quickly,’ Géraldine laughs. It makes the marine experience all the more realistic and hopefully the impact bigger. ‘We’ve run several studies now, about that difference between VR and underwater VR for marine education. It looks quite promising,’ Géraldine says.

For who wants to learn more, she’ll be presenting the results of her findings at the EMSEA conference in Croatia this September.

The benefits of (underwater) VR

VR can support ocean literacy in different ways. First, there is the connection that is created between the marine environment and the person experiencing the virtual underwater world. Especially for people who don’t have the financial or practical possibility to experience the sea in real life, this may help bringing about the feeling of connectedness and, eventually, care. The emotional aspect is quite important here. The people involved in the underwater VR experiment expressed very powerful emotions like fear but also empathy and belonging.

Second, it offers opportunities for environmental education. For example, at Stanford, the Virtual Human Interaction lab developed an Ocean Acidification Experience, where you follow a molecule of carbon dioxide from a car to the ocean. Then, you take on the role of a scientist doing a species count. ‘So, you see a reef around you, where you can physically walk around. You also have a bucket with flags, and you have to put a flag next to each sea snail you see. Then you are transported to an acidified reef. It’s the same kind of reef, but with a lower pH. There, you do the species count again, but this time, you walk around and you hardly see any sea snail. Then the voice in the headset tells you about ocean acidification and the impact of our behaviour on the sea and its biodiversity,’ Géraldine explains.

However, before scaling up (U)VR, Géraldine finds it important to first research the benefits (or possible drawbacks) of the medium. ‘There are so many tech-optimistic people who believe this new technology is going to drastically change the way we learn and experience the world. But for now, the equipment is still very expensive. And more importantly, before we even think about how to scale up, we need to study that technology, how it can contribute to the field of marine education, in what context. We first need to research what it may change in terms of people’s connection and relationship with the ocean,’ Géraldine states.

Also, a 10-minute VR-experience cannot replace a book, a lecture, a teacher or a live beach activity. ‘It’s just a tool,’ Géraldine says. ‘A tool like many others.’

However, that the technology can trigger an emotion and start a spark, she does not deny. A couple of months ago, Géraldine’s team was at a science festival where they had members of the public joining the underwater VR experience. There was a Ukrainian refugee, who had booked a session but couldn't swim and who only spoke a little bit of English. Géraldine joined her in the water, taking her hand. Soon enough, the woman let go and went to discover on her own. After ten minutes, she took off the mask and was absolutely astonished by what she had seen. ‘Amazing!’ she yelled. ‘To see that transformation, from being fearful to being absolutely overjoyed… That might very well have been the most beautiful moment in my career,’ Géraldine smiles.

Top tips for Ocean Literacy organisations by Géraldine Fauville

- An important component of ocean literacy is: how do we make people change behaviour? We know that knowledge in itself doesn't do much. Emotions and connectedness can do more.

- We need to truly listen to people, listen to their connection with the ocean, or their lack of connection. And then, we need to use that. We need to build from a child’s fascination for a certain shark, of from the disgust of someone to go into the water. We need to listen to that specific person and understand them. Where does their fear come from? Where do their barriers come from? And then work from there, to be as customised as can be.

Text by Anke de Sagher for EMSEA

Photos provided by Géraldine Fauville

More on Géraldine Fauville

Personal website · X · LinkedIn · Website University of Gothenburg

Want to join the community? Find out how to become an EMSEA member!